Farewell to the mother of all depressions

- Published

- comments

The British economy is now officially 0.2% bigger than it was at its last peak, in the first three months of 2008.

So, as I mentioned earlier this week, Britain's longest depression since serious record-keeping began is now officially over.

Plainly this is good news (and do read my earlier note for reasons why you probably won't be feeling as prosperous as you did six years ago, or why the actual moment of depression's end will probably turn out to have been a bit earlier than currently thought).

Here's one positive knock-on: an unexpectedly large growth in profits announced by Royal Bank of Scotland this morning - which has boosted RBS's capital and share price, and perhaps means taxpayers' losses on the eventual privatisation of the bank won't be as ginormous as feared.

So what kind of recovery has this been?

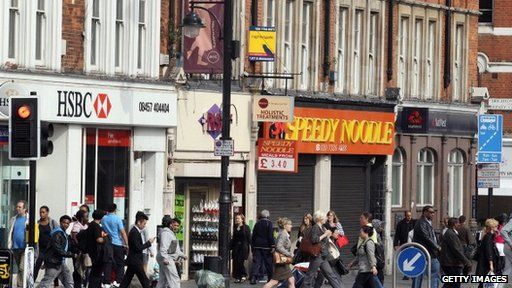

Well it has been completely dominated by our service industries.

Which should not be a great surprise since they contribute more than three quarters to our national output.

Glass half full?

Without a resurgence in services, there would be no prospect at all of the UK regaining the income lost in the great crash of 2007-8.

But nonetheless many will be slightly depressed that although the service economy is now just under 3% bigger than it was at the peak, manufacturing is still more than 7% smaller, and the production industries as a whole have been diminished by 11%.

As I have bored on about for a while, although it is heart-warming to see UK manufacturing growing right now, there has been no rebalancing of the economy back towards the makers.

Also, within services, the contribution of shoppers to the recovery remains immense - and the retail trade made the biggest contribution to the latest quarter's services surge.

That suggests we may be at a premature end to households' attempts to strengthen their finances and pay down debts - and shows that growth in the economy remains perilously sensitive to the cost of money.

Or to resume my habit of telling you stuff you know, the scale and pace of interest rate rises will have a hugely important bearing on the sustainability of this recovery.

That said, the glass is definitely half full today.

Boom and bust

The UK is growing much faster than all the UK's big rich competitor economies, including Germany and America.

And although it has taken us much longer to grow above the past peak than it did for the US and Germany, the original contraction in our economy was much sharper than for them - because we were so dependent on our bloated, hobbled banks.

Here is the measure of how and why, for the UK especially, a depression caused by a banking crisis is so much worse than other economic contractions.

We are now 25 quarters, or six years and three months, since the slump began.

After 25 quarters had elapsed from the very painful downturn of 1979, the contraction that defined the early years of Margaret Thatcher's government, the British economy was 8% bigger than its previous peak.

And 25 quarters after the recession of 1990, that caused by Nigel Lawson's boom and bust, the UK was 16% larger than its past record level.

Today, 25 quarters on from a great crash that many blame on Gordon Brown's complacent attitude to City regulation, the economy is more-or-less the same size as it was.

Lest we forget, this has been the mother of all modern depressions.