Elections highlight economic divisions in Brazil

- Published

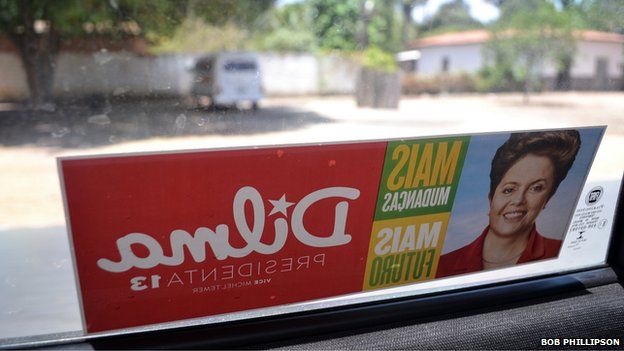

The Workers' Party campaign truck crawls slowly through the streets of Belagua. Painted red, the vehicle is covered in stickers of a beaming Dilma Rousseff and on the back a large set of speakers is blaring out the campaign jingle.

The truck's presence seems wasted. In these parts of rural Maranhao, Dilma gets nearly 100% of the vote.

The reason for that is simple. In Belagua, 83% of people receive what is known as the bolsa familia, a family allowance introduced by the Workers' Party just over a decade ago to help people escape extreme poverty.

Marinalva Saminez Dos Santos is one of those who benefits. She shares a simple one-roomed mud house with her husband Jose Domingos and nine of their 11 children.

Neither Marinalva nor Jose Domingos can read or write. The $300 they receive from the government each month is their only source of income.

"I can buy food, sandals and school uniform for my children, it really helps me," she says. The family still lives below the poverty line but survival was even harder before.

While Marinalva says she will always depend on the bolsa familia to survive, her neighbour Ana Lucia Alves Sousa says the scheme has allowed her to escape poverty.

As well as receiving money every month, the government helped her to study.

Two years ago she felt she had enough stability in her life to stop receiving her benefits. She is now a Portuguese language teacher and has recently opened a little shop in the village with her husband.

"I cancelled my bolsa familia, but in truth I'm still benefitting through the goods I am selling," says Ana Lucia, referring to the extra goods people are buying with the income they now have.

Lifelines for business

Government help is not confined to families. Under the Workers' Party, regional development banks have offered cheap loans to businesses and that has enabled the regional economy to grow.

Iwaldo Calixta de Sousa is in his seventies and lives in the small town of Nova Olinda, about six hours' drive from Belagua. He started his household goods store 41 years ago with his wife, Rosa.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, Brazil suffered a period of hyperinflation - it was during these times that his business collapsed and lost everything.

But when Dilma Rousseff's predecessor Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva became president in 2002, he says things got easier. He has opened two branches in neighbouring towns.

"I never gave up," says Iwaldo, despite having to go and work in the country as a market-seller. "Because of credit, I'm back here again."

His business has been helped by initiatives such as Crediamigo, one of the largest microfinance programmes in Brazil and run by the regional Banco do Nordeste.

Under the scheme, a group of businesses can club together for a loan and they are all responsible for repayment.

Agreements with banks have also enabled Iwaldo's business to give clients the option of paying in instalments.

Iwaldo's son-in-law, Jairo, agrees that under the Workers' Party, financing has got far easier.

Although interest rates have been creeping up in the past few years, they both fear a new government coming in and a return to the old days of little credit, high interest rates and soaring inflation.

Industrial hubs

The northeast has become synonymous with Brazil's growth story - generous welfare programmes as well as labour legislation like the minimum wage, have had a disproportionately positive effect in poorer areas of the country.

As well as that, financial incentives for companies to relocate to the region have seen new industries pop up such as car plants in Pernambuco and steel manufacturing in Ceara.

"The northeast is a different country. One that is being rediscovered by Brazil," says Hector Gomez Ang from the World Bank's private sector lending investment arm, the International Finance Corporation.

The group is supporting numerous projects in the northeast, he says.

"It is a very large region. The northeast is a series of mini-countries - each state could be a small nation with very different challenges. Each one has leveraged its own strengths to create its own development model."

Disillusioned business community

But the business community in Maranhao says the state lacks the development that has been seen in other states.

High prices for commodities like soya have helped the economy grow but investment elsewhere - in areas such as tourism - is lacking.

"If you look at the state of Maranhao in comparison with the other states, we're at least 10 or 15 years behind them," says Luzia Rezende, who heads up Maranhao's Business Association.

While she is not against bolsa familia, she thinks the government needs to spend money in other areas.

"Of course, lifting people out of poverty is really important. But at the same time, we have to educate people - people need to be well-fed first but they also need to go to school."

With the economy in recession, Luzia says her members are worried - and that translates into votes for business-friendly Aecio Neves.

This part of Brazil has changed hugely in the past decade, and the sound of donkey carts has been replaced by the whirr of motorbikes.

Yet these elections highlight the huge economic divisions in Brazil.

When people vote on Sunday, they will have to decide whether to vote to keep in a government that has focused on lifting millions of people out of poverty, or whether to vote for change and a renewed effort to get Brazil's economy growing once again.

- Published24 October 2014

- Published13 October 2014

- Published9 October 2014

- Published6 October 2014