Why Dara the Prince has a modern message

- Published

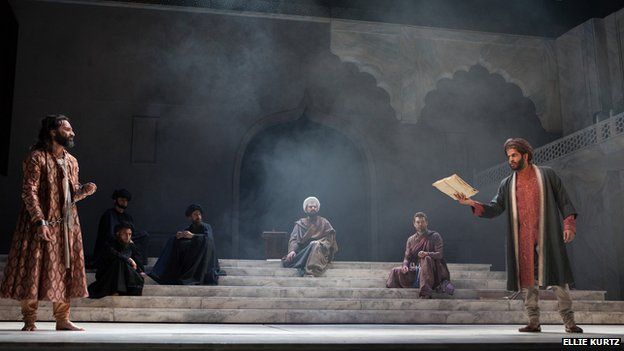

Dara the Prince, currently on at the National Theatre in London, presents the brutal struggle for power in 17th Century Hindustan. The story has similarities with a classic Greek tragedy, where a prophecy in childhood divides a family and sows seeds of hatred and mistrust.

When Emperor Shahjahan, in the presence of his children, asks a faqir (a spiritual believer) who among them would deceive him, the faqir points towards his second-born, Aurangzeb.

On the face of it the play is an account of Aurangzeb taking away the throne from the heir Dara and legitimising his own place as ruler. However, it has a message painfully relevant to the present.

Religion as a means to power

Unable to remove Dara from the throne, Aurangzeb uses religion for his motives. The audience today and in any age might find similarities with how political motives are also achieved through manipulation of religious dictates. Dara stands in a Sharia court desperately denying his sins, which include writing poetry, enjoining religious tolerance and removing social stratification.

The battle is not between Dara and any religion - but Dara and one definite interpretation of Islam. Dara's defence is the defence of the 17th Century Muslim, but also a defence of the modern Muslim desperately pleading the case of Islam's message of love and peace.

Today, extremist forces such as the Taliban and Islamic State hold their own courts and sentence people to death for not following their definition of Islam; much like the mullahs of Aurangzeb's court. Dara is branded an infidel by the prosecutor for reading the Hindu and Sikh holy books. In return, when Dara asks if the prosecutor has read those books, his question is dismissed.

Love

Dara the play also explores the different kinds of love that exist within society; some forbidden and some that have the power in them to unify differences of caste and religion.

In the 17th Century sub-continent the minority Muslim Mughal family ruled over the Hindu majority. At its heart the play is a tragic narration of the political failure of the Mughal Empire. Aurangzeb not only removed the heir to the throne, he also used his religious fervour to further segregate a divided society.

While Dara believed in the divine spirit emanating from all religions, Aurangzeb thought it to be contained only within Islam. Through Sufism and an understanding of the Hindu and Sikh Holy Books, Dara advocated love for all. He advocated multiculturalism and understood the need for dialogue in religion. A lack of this compassion led Aurangzeb to execute policies laced with religious extremism which resulted in hatred for him among his own people.

Aurangzeb is shown to have fallen in love with a Hindu girl, Hira. Tragically she dies and Aurangzeb is bereft with anguish. The play highlights how such love beyond the religious divide would have been impossible in a deeply divided society. With recurrent images of Hira flitting through his mind, both Aurangzeb and the audience feel compelled to think how different he would have been had he not lost his love.

The play also alludes to the loving marriage of Shahjahan and Mumtaz Mahal; for which the Taj Mahal stands today as a powerful symbol. A union of such love, translated into utter hatred in the next generation, also evokes pathos.

Place of women

In the sub-continent of the 17th Century women of the royalty were normally confined to their quarters and were thought to have little involvement in the running of the state. However, the royal family that Dara belongs to is different. Women are not only in the forefront of the power struggle, they are also strong influences.

We see one sister, Jahanara, in the role of a matriarch, protecting her father but also trying desperately to bridge the divide between the two brothers. We see the other sister Roshanara fuelling the hatred between brothers and in fact encouraging Aurangzeb to make Dara go through the unfair trial of the Sharia court.

As he gives his defence in court Dara also gives his opinion on an issue that is part of contemporary debate: the hijab. While defending his moderate thought, Dara looks up to the chambers where Aurangzeb and Roshanara are watching the trial behind a curtain. As the prosecutor snubs him for calling out to his sister, Dara explains that the veil is mandated only for the wives of the Prophet and not for all women in Islam. The debate around the hijab is just as controversial today as it was in the 17th Century.

Women are a constant presence in the play, whether it is the memory of Mumtaz Mahal, Hira's dancing presence, Roshanara fuelling the fire of hatred, or Jahanara resolutely facing imprisonment and standing by Dara.

What makes this play relevant now is that Dara's character to this day evokes divided opinion within the region; some hail him as the modern thinker, eager to unify society, while others chastise him still as an infidel who violated religion. It is almost as if Dara still stands before a court awaiting judgment on his beliefs and his character.