Does a death sentence always mean death?

- Published

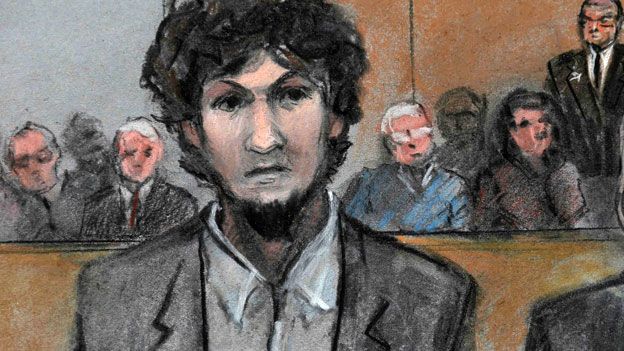

Boston bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev has been sentenced to death by a federal jury in the US for his part in the attacks on the 2013 marathon. But only a small proportion of those on Death Row are actually executed.

Between 1973 and the end of 2013, 8,466 people were sentenced to death in the United States, and 1,359 - about one in six - were executed.

"It's a death penalty in name only," says Frank R Baumgartner, a political science professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

He has studied the fate of people on death row and discovered that as of 31 December 2013

- 2,979 remain on death row

- 392 had their sentences commuted

- 3,194 had their death sentences overturned

Of those who have had their sentences overturned, the Death Penalty Information Center, estimates that 152 have been exonerated.

One conclusion that can be drawn from these figures is that, as Bryan Stevenson, executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, put it on BBC Radio 4 earlier this year: "For every nine people that we have executed in America, we have identified one innocent person on death row."

Some people, of course, have died on death row of natural causes or suicide.

The proportion of people executed varies from state to state. Eighteen out of the 50 states have banned the death penalty, and just this week the state of Nebraska legislature voted in favour of abolishing it.

Of the 32 states where the death penalty remains in force, Baumgartner points out that Virginia executes a higher proportion of those sentenced to death than any other - about 72%.

"They are very strict about limiting appeals to 12 months. If your appeals aren't filed within 12 months, your case will be considered to be final.

"That's the only state to have such rules, and the only state that has more than 50% of cases carried out to execution.

"There are many states where it is extremely rare."

California has executed about 1%.

"They simply don't carry out their executions," Baumgartner says.

But as well as individual states, the federal government can try people, and sentence them, for federal crimes. This is what has happened in the case of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.

Although he committed the crimes in Massachusetts - a state without the death penalty - he was convicted and sentenced by a federal court.

But between 1973 and 2013, the federal government has only executed three people out of 71 sentenced to death. There are 56 people awaiting execution.

So the chance of being executed by the federal government is low, says Baumgartner.

Across the world, the number of countries using the death penalty has been in decline, says Prof Carolyn Hoyle, director of the Centre for Criminology at the University of Oxford.

More than half of all countries have officially banned the death penalty, and less than a quarter have used it in the last decade.

"If you look back to 1988 only 35 countries had abolished the death penalty. Today, 107 have abolished the death penalty," she says.

"Another 52 countries haven't executed anyone in the last 10 years, so they retain it on the books, but they are not actively using it."

The UK stopped using the death penalty in 1965, but retained it as a punishment for arson in the Royal Dockyards until 1971, and for treason and piracy with violence until 1998.

Only 39 countries have executed someone in the past decade, most of them in Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

The US has by far the most developed appeals system according to Hoyle. In contrast, some countries have "speedy courts" and limited options for appeal. Some do not allow the accused to take part in the trial and may coerce suspects into making a false confession.

There are no available figures for the number of people in these countries who have been sentenced to death and subsequently had their sentences revoked.

But there is anecdotal evidence of miscarriages of justice, says Hoyle.

"In China, a very high-profile case a few years ago was of a man who was convicted of killing his neighbour. The neighbour wandered back to the village 10 years later alive and well.

"That was a case where not only was he not guilty, there had not actually been a crime."

Listen to More or Less on BBC Radio 4 and the World Service, or download the free podcast.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.