100 Women 2015: How does the brain cope with Tinder?

- Published

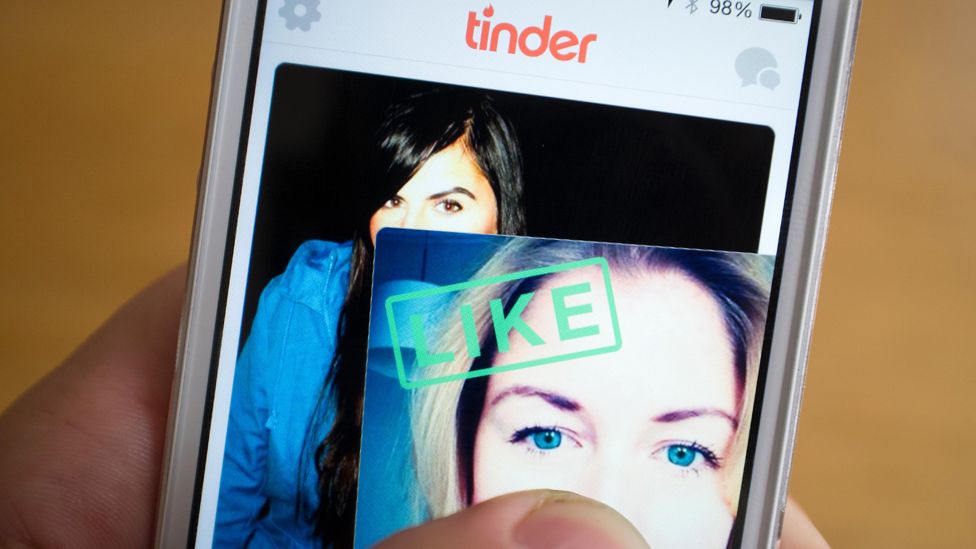

Apps like Tinder have transformed dating. How well-equipped is the human brain to deal with this cultural shift?

The first man Sally met through Tinder seemed promising.

"We had a really good repartee," Sally says. They went on two dates and chatted constantly, exchanging about 80 messages.

And then, with no explanation, he sent her a text message cutting her off.

"Because this guy had no connection to me, he had the ability to be brutal," says Sally, 30, a make-up artist from London. She joined Tinder two years ago after a relationship finished and recently signed up to happn, another app which matches users to people they have physically crossed paths with.

But over time she's grown wary of dating apps. "That whole idea of instant gratification has ruined sex for an entire generation of women," she says.

Users of Tinder see a potential match and if they like the look of them, swipe right on the screen. If they don't, they swipe left, and that person is gone. The app, which according to The Drum is responsible for eight billion connections across 196 countries, is the most popular of its kind in the world.

Users swipe 97,200 times per minute and the average user spends 11 minutes a day looking through the profiles of potential matches.

But it's common to hear people lament the kind of behaviour Tinder supposedly encourages. Headlines warn of a "dating apocalypse", which "kills" or "swipes out" romance while others decry it is tearing society apart. Young women complain that their inboxes are filling up with unsolicited and unwelcome pictures of strangers' penises.

"It's like an Argos catalogue, having everyone available - it's the personal equivalent of hundreds of men standing in a pub all telling you how much they like you but pushing past you the moment the next hotter girl comes in," says Sally.

Alongside Tinder, online dating is hugely popular. The site eHarmony has more than 66 million users and 7.3 million messages are sent through OKCupid every day.

Human beings have evolved over two million years to develop the most complex cerebral system in existence - and to be largely monogamous. But how well equipped are people to deal the anonymity and range of choice dating apps allow?

This year's season features two weeks of inspirational stories about the BBC's 100 Women and others who are defying stereotypes around the world.

Like us on Facebook and follow us on Instagram using the hashtag #100Women. Listen to the programmes here.

There's nothing new about looking at pictures to decide on a partner, says Lucy Brown, clinical professor at the Einstein College of Medicine in New York, who has co-authored several papers on the neurobiology of romantic love.

Henry VIII commissioned a portrait of Anne of Cleves to help him decide on her marriage potential, says Brown. But she warns this isn't a particularly effective way of choosing someone.

Humans are wired to judge people after seeing them "in movement", she says, rather than through a mixture of still images and messages on a screen.

"It's very dangerous - you can't tell much from a photograph," Brown says. "The human brain is set up to take in details about the way someone moves or the way they smile." So it makes sense to meet as soon as possible.

It takes on average three years of living with someone before they fully reveal themselves, she says. Apps like Tinder and happn, however, are better known for facilitating short-term relationships.

And this is one of the most commonly expressed fears about social impact of dating apps - that the promise of endless choice encourages people to chase the thrill of multiple short-term flings rather than work at a long-term partnership. "That's the worry - that women are that accessible," says Sally.

There is evidence to suggest that dramatic chemical changes go on inside the brain during the early days of a relationship.

A study conducted by the University of Pisa in 1999 found that levels of the brain messenger chemical serotonin in people going through the initial romantic phase of love were comparable with the levels in those who have obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

And in 2007 scientists at the University of Basel found this early stage of passion is comparable to hypomania - a state of heightened energy, lower inhibitions and a decreased need for sleep.

Professor Bianca Acevedo, a research fellow at the University of California Los Angeles, says there's a surge of dopamine - a chemical which transmits signals in the brain - in the first stages of a relationship, which makes people excited. This unconscious reward system is something to which people need to be addicted "for our survival".

She adds: "They need the extra energy to engage in the relationship and all the things you are doing, like staying up talking all night, and when you are not with the person you are constantly thinking about them.

"We did see those activations in people newly in love - associated with anxiety and obsessive-compulsive."

It doesn't necessarily follow that dating apps are turning people into commitment-phobes. Withdrawing from a relationship quickly after a period of intensity is likely to be a personality trait, Brown says. It is, however, a personality trait that online dating enables.

And when things seem super-high octane shortly after meeting someone, Brown urges caution. "People may have three or four others they are looking at - perhaps someone else pops up," she adds.

Brown says it is really important at this stage of a relationship to "know thy brain". She adds: "Know that nature is throwing you a bit out of control."

This doesn't guarantee an end to bad dates, however, or to solve another facet of internet dating, according to Sally - how to extricate herself from one as quickly as possible whilst remaining polite.

She says: "There is nothing worse than sitting there going: 'Oh, this restaurant is ruined because I shared it with you.'"

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published25 November 2015

- Published19 November 2015

- Published28 November 2015

- Published27 November 2015