Mick Fleetwood on the early days of Fleetwood Mac and why he's a terrible drummer

- Published

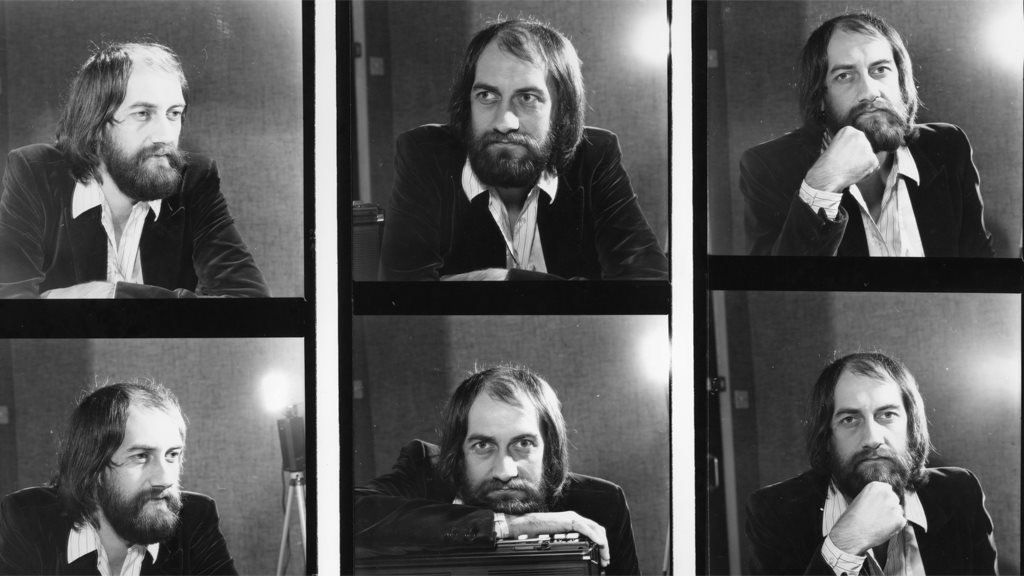

Mick Fleetwood is the backbone of the band that bears his name; the man who kept Fleetwood Mac rolling through the best and hardest of times.

In the early days he was their manager, hiring and firing musicians like a soft rock Alan Sugar.

By the late 70s, he was the bandage that stopped them falling apart amidst drug abuse, infidelity and betrayal.

And sitting behind his "back to front" drum kit, Fleetwood is the band's beating heart, constructing dozens of unforgettable rhythms - from the syncopated shuffle of Go Your Own Way, to the fidgety cowbell riff of Oh Well.

But surprisingly, the 70-year-old doesn't rate his own drumming.

"There's no discipline," he says. "I can't do the same thing every night."

Anyone who's listened to the deluxe edition of Fleetwood Mac's Tusk will know otherwise. There, you can hear multiple outtakes from the title track, with Fleetwood sitting doggedly on the song's distinctive groove for more than 25 minutes.

Still, he insists: "I am very not conformed, I change all the time."

The confession is prompted by a discussion about Fleetwood's lavish new picture book, Love That Burns, which chronicles his early career and the first incarnations of Fleetwood Mac.

It's being released 50 years after the band played their first show: A 20-minute set at the Windsor Jazz & Blues Festival alongside artists like Cream, Pink Floyd and Jeff Beck.

Back then, they were a hard-edged blues combo, working under the guidance of guitarist Peter Green - who, like Fleetwood and bassist John McVie, had previously played in John Mayall's Bluesbreakers.

Green called the group Fleetwood Mac "because I knew I was probably going to leave," he later recalled, adding: "I always wanted Mick and John to have a job."

In the late 60s, the band enjoyed hits with Albatross, Oh Well and Black Magic Woman (later covered by Santana) before the ominous The Green Manilishi presaged Green's descent into drug-induced psychosis.

It's a period of the band's history that's frequently overshadowed by their wildly-successful 70s incarnation, the one that produced Rumours and Tusk, and that's what Fleetwood hopes to correct in the new book.

"The other thing is so big and so famous that this [story] could just get swallowed up," he says, "I'm happy that at least there's something that says, 'Hey, this is how it all started.'"

As the story begins, the young Fleetwood is a three-time runaway from boarding school, who's been cut loose by his parents and is barrelling around London in a second-hand taxi, dropping in and out of blues bands as he learns his craft.

"In those days, if you had a drum kit that was worth something it was almost more important than if you were a half-way decent drummer," he laughs.

"So if you had the drums and the taxi it was like, 'Yeah, let's give him the gig!'"

'Monumental scolding'

One of his first paid jobs was with The Cheynes, who were hired as the backing band for visiting blues legend Sonny Boy Williamson when he played London's Marquee Club.

Unprepared for Williamson's tendency to improvise, the band completely lost their way and got a "monumental scolding" in front of the audience.

After bouncing between gigs for a couple of years, Fleetwood ended up in John Mayall's Bluesbreakers, replacing their previous drummer, Aynsley Dunbar.

"Aynsley is a brilliant drummer," says Fleetwood. "Technically, he's in a whole different league than I am, but he was probably getting a bit too clever.

"The band didn't want any more drum solos, so he was out and I was in."

That didn't go down well with the audience, however, who started chanting "Where's Aynsley?" every night.

"And I always remember, in the early days, John [McVie] came to my rescue and basically came to the microphone and told them to shut up."

It was a beginning of a beautiful friendship. Fleetwood and McVie not only gave their names to Fleetwood Mac, but they are the only constants in the band's ever-changing line-up.

In the book, Fleetwood says of McVie: "Musically, he helped me survive whenever I was drowning." And it's this comment that prompts the revelation about the drummer's supposed lack of skill.

"For a while, he thought he could train me into doing the same bass drum pattern every night but I couldn't... because of the way my mind works," he explains, "so John learned to push all his notes around what I do."

"It's become this weird thing. It's not really how a rhythm section should work. They're supposed to be doing exactly the same thing at the same time. I'm doing different stuff and he's falling in between the gaps."

After three years of success, Fleetwood Mac's future was jeopardised when Green quit, giving away most of his earnings in the process.

The guitarist's mental health deteriorated soon after, and he was eventually diagnosed with drug-induced schizophrenia, spending long periods in psychiatric hospitals and undergoing electroconvulsive therapy.

"I don't know why I left the group in the end," Green writes in Fleetwood's book. "I know that people looked at me like I was in a dream. I could tell that, even at the time."

Fleetwood describes Green's decline with tenderness and regret. It's clear he still feels responsible, in some way, for not spotting his friend's illness sooner.

"I wish we had been better equipped," he tells me. "Maybe we could have seen something that could've helped - not to keep him in the band, but to help this person through the beginnings of a very emotional ride that, really, he's still on as we speak.

"It affected his life in a very dramatic way," he adds. "I don't think he was treated right for what turned out to be his illness, but he's healthy now and doing ok. I'm going to go and see him on Sunday, in fact."

After Green left, Fleetwood Mac floundered for a while, before recruiting John's wife Christine McVie - who was already a solo star in her own right.

She went on to write some of the band's most memorable songs - Songbird, Don't Stop, Over My Head - and remains part of the line-up today. But the band's fortunes really turned around in 1974, when they were joined by two young American singers, Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks.

It's at this point that Love That Burns draws to a close. Fleetwood says there are plans for a Volume Two, which promises to go behind-the-scenes on Rumours, the seventh best-selling studio album of all time, and one which was recorded as the personal lives of Fleetwood Mac's five members unravelled.

"That will be a big monster," laughs Fleetwood.

"I don't know when we're going to do it, but that story needs to be told."

Love That Burns - A Chronicle of Fleetwood Mac, Volume One is out now via Genesis Publications.

Follow us on Facebook, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk.

- Published10 July 2017

- Published14 January 2014

- Published5 November 2014